Recently we returned from a retail conference where we highlighted to attendees the differences in perception and attitudes they have toward location data, depending on whether they are using it in their personal or professional lives.

This was the type of conference where those big-box and household-name retailers you see every day send their people in charge. They meet and discuss different ways to sort out the massive amounts of data they capture from today’s digital world. Their main purpose? Turn that data into hard results.

As everyone sat in a large room gulping down burnt coffee, chewing on bagels, and adjusting to time zone changes, we brought up a subject that is foreign to some, familiar to others, and uncomfortable for all: data privacy. The elephant in the room for big data. The one subject that everyone in the room had heard about, needed to deal with, but definitely did not want to talk about.

Should you check out check-ins?

We asked this room of powerful people to take off their retail hats and start thinking about themselves as individuals. Then we had them think about their journey to the conference, in geographic terms. We had them write down everything they had done the previous day that had given away their location information—whether or not by choice.

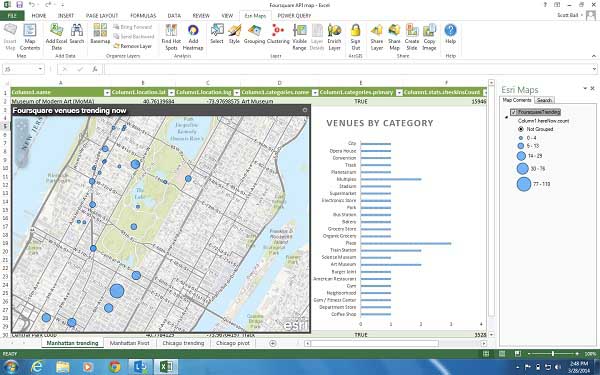

There’s the obvious: check-ins to Foursquare via the app on their smartphone and tagging their locations on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter. Some had shared their information by opting into free Wi-Fi. Others had comparison shopped and looked at prices nearby. One thing they all had in common? Every single person had shared his or her location via multiple sources throughout the course of just one day.

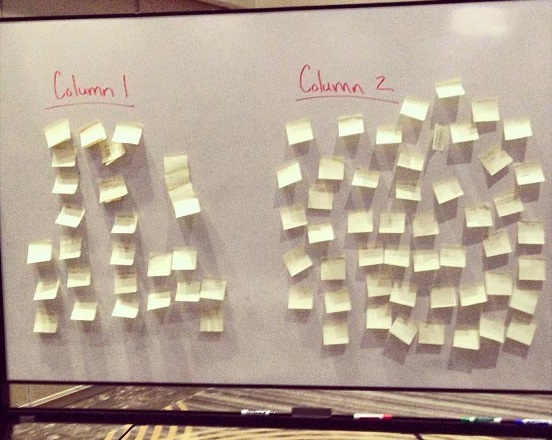

Two simple columns—”I would share this information” and “I would not share this information”—were created. One by one, attendees reorganized their actions on the whiteboard, located at the front of the room, showing everyone how they felt about sharing.

Staying in the customer comfort zone

Here’s where it starts to get interesting. We read out loud all the items that were not to be shared but asked the group to put their retail executive caps back on. As retailers, would they want the information that they themselves had said they were not willing to share?

Hands were sheepishly raised. Some questioned whether they should move their responses to the opposite column. It was as if there was some shame in asking for information that would help them answer the most important question in retail—Who are my customers, really?—if it also exposed where they were and when.

As an industry, we need to look at solutions that give retailers the information they want without making consumers uncomfortable. There are a few ways to do this. Often it comes down to seeing when it is valuable to understand who the individual is, versus the crowd.

When does the actions of one trump the actions of many?

Often the bigger behaviors of “digital swarms”—moving between places, shopping at stores, sending out location-based transactional data—is more valuable than individual behaviors. Geography offers a great way to aggregate information and activities, keeping individual actions anonymous while identifying larger patterns.

If understanding individual transactions, however, becomes more important, a suggestion shared among the group during the event was that although some individuals may not be comfortable sharing information all the time, they would unquestionably share it if they had an incentive or convenience for their effort—a retail quid pro quo, as it were.

One example is PowerDash, a free, downloadable game created by Esri partner Taqtile in collaboration with AMP Energy, racing legend Dale Earnhardt Jr., and 7-Eleven. When game players visited participating 7-Eleven stores around the United States and then scanned cans of AMP Energy, they could unlock special tips and tricks that could help them win the game and a variety of prizes.

This innovative marketing program drove more than a digital car on a virtual race track. Distribution and endcap displays of the latest flavor, AMP Energy Orange, were up 70 percent at participating 7-Eleven stores from March to May 2014 when the program ran.

Shall we opt-in?

Yes, 7-Eleven received information about what the shoppers did in its stores. But the shoppers were able to collect points playing the game that were then used to win Ernhardt memorabilia and autographs, AMP Energy swag like snow pants and jackets, and a VIP NASCAR experience.

A recent article in Street Fight (“Strategies for Overcoming Privacy Concerns with Indoor Navigation Apps“) went over some of the solutions to today’s privacy issues. The magazine brought up some important points, including the idea of urging shoppers to opt-in.

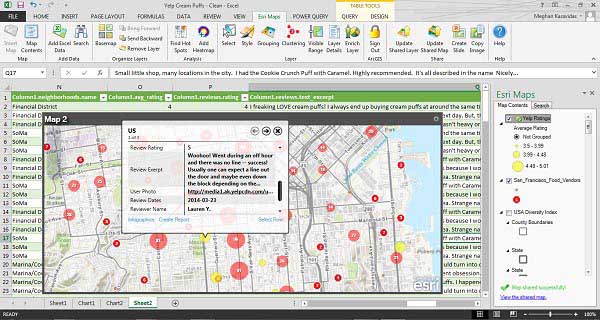

Using this concept of pushing consumers to opt-in, retailers are mining social media information (including check-ins, reviews, and mentions) to understand how well they are operating, the sentiment around their brand, and the underlying needs of their customers, down to each store’s location. Using this information, retailers can even begin to tailor their marketing activities based on real-time data being fed into these systems.